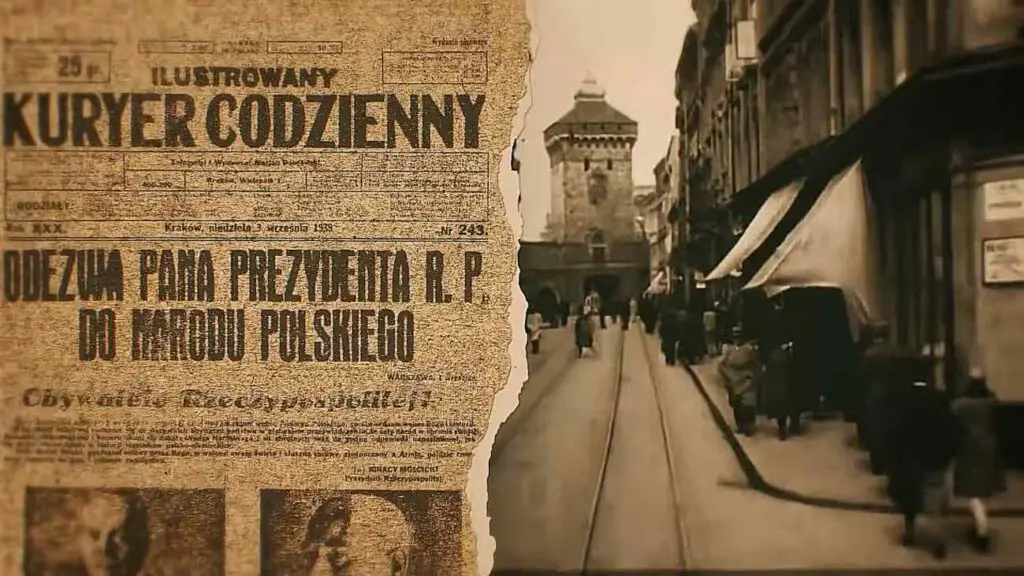

Imagine stepping back in time, to Kraków during World War II. What was life like under German occupation? It was a period of immense transformation. Kraków, home to merely a thousand Germans pre-war among its 400,000 residents, saw a sharp increase in German population. By 1944, over 50,000 Germans lived near Wawel, including many soldiers returning from the front.

If you want a visual, picture this: every fifth person strolling down Grodzka or Floriańska street was a German. Compare this to Warsaw, where the ratio was one in twenty.

- You definitely need to read about Kraków Ghetto: Krakow Ghetto – A Journey Through the Shadows of World War II

The Role of Kraków in the Resistance During WW2

Kraków wasn’t just a place overtaken by Germans, though. I think it’s important to note that it was also the second most important center of Polish resistance – politically, intellectually, and militarily. When reminiscing about the city’s history, I am convinced it’s crucial to remember its resistant spirit. This was no passive city. Despite the foreign rule, it became an unwilling, alien, but still essential capital.

- I think you also should read this article I wrote: Catholicism in Poland – How its History Shaped Country’s Identity

Kraków’s Place in the Third Reich’s Vision

Kraków held a unique position in the Third Reich’s vision – it was destined to be the racially pure metropolis of the German East. Being there, you need to know the grim plans they had for the city. After the horrific extermination of over 60,000 Jewish Cracovians, the city was to be resettled by Cracovian-Poles, providing cheap labor for German enterprises.

↳ PRO TIP: Do you like traveling? Then before you buy any ticket or book an attraction, check if it's available in this worldwide Viator Database. You may save a lot of money and time. No need to thank me :)

The left bank, including landmarks like Wawel and the Market Square (rechristened Adolf Hitler Platz), were envisioned as purely German spaces. I believe it’s worth saying that Nazi propaganda framed this not as a takeover, but as a reclaiming.

They promoted Kraków as an ’uralte deutsche Stadt’, an ancient German city, given its history of German influence and notable figures like Copernicus and Veit Stoss who had left their marks here. This narrative attracted a diverse range of settlers, from merchants to officials, young women to soldiers, all contributing to the growth of a new, German metropolis.

- There is another interesting article about Kraków Ghetto: Walking the Krakow Ghetto Walls – The Footsteps of History

The Nazi Propaganda About Kraków During The War

So, here’s the rundown: Nazi propagandists effectively made Kraków seem like an Eldorado, a land of opportunity. People like Oskar Schindler, officials seeking a peaceful job away from the frontlines, young women aiming for independence, and even soldiers of the Wehrmacht, Luftwaffe, and Waffen SS who sought leisurely breaks, were drawn to the city. They brought their wives, children, mistresses, parents, and employees with them.

Together, they formed the nucleus of a new, purely German metropolis. I can tell you, it was a period of upheaval and change, reshaping Kraków’s identity forever.

Let’s dive into the daily life of German occupiers in Kraków. What was their experience like? What were their likes, dislikes, surprises? Did they feel at home in the city? I am convincd you might be wondering, did they interact with the local Poles and Jews? Could they have been oblivious to the widespread terror, considering Auschwitz was just a few kilometers away? What remnants of their presence do we see in modern-day Kraków?

- I suggest you also read this article: Visiting Auschwitz-Birkenau Camp: A Somber Reflection on the Holocaust

Discovering the Occupiers – An Exhibit in Schindler’s Factory

Monika Bednarek and Katarzyna Zimmerer tackled these intriguing questions in their exhibition „Occupants. Germany in Krakow„. If you’re a tourist in Kraków, I know you’d love to visit this exhibition, which is located in the frequently visited Schindler’s Factory, running until October 29th. This small, pioneering exhibition provides unique insights into a topic that has not yet been deeply explored, making it all the more exciting.

Packed into a compact temporary exhibition hall, the display includes numerous photographs. These photos, hitherto unknown to the public, were generously donated to the Historical Museum of the City of Krakow, primarily by German donors. These new additions undoubtedly highlight the international success of the museum, which opened in 2010 in Schindler’s Factory.

Unseen Photos of Kraków

The heart of this exhibition? Undoubtedly, the photographs. They provide a startling view of the city through the occupiers’ lens. It’s a moving, unsettling, and somewhat schizophrenic experience. For instance, you’ll see a cheerful couple in flirtatious mood, her donning a hat and jacket with the German Red Cross emblem, him in a sharp Wehrmacht uniform.

Having just left Szewska Street, they stroll through a bustling Market Square. Perhaps they were heading to one of the Pole-restricted cafes, like Feniks or Literatisches Kafehaus.

Yet, among these lively scenes, there are unsettling ones as well. Another couple, seen from behind, carefully peruse a large poster. Such posters were common during the occupation, announcing restrictions for the local population, instilling fear, and listing victims of mass executions.

Scenes from a War-Time Picnic

The exhibition also features more idyllic scenes. One photo shows a group of elderly soldiers with slight „beer” bellies, crossing the Vistula from Tyniec to Piekary on horseback. It’s a picture-perfect moment – picnic vibes, great weather, clear waters, a picturesque landscape. It’s almost like they were on a vacation.

In another snapshot, officials from the German Post Office East pose joyfully in front of the AGH University of Science and Technology’s main building, home to the General Government authorities since 1940. The women appear liberated and happy, free from their typical roles as German mothers.

Kraków in the Lens of Occupiers

These private, sentimental snapshots serve as poignant souvenirs of the occupation. They paint a picture of Kraków as a place where Germans could feel „almost at home”, finding job and career opportunities, suitable accommodation, and attractive leisure spots.

However, these photographs also underscore the enormity of the Third Reich’s colonial project for Kraków and the extent of its progression. They are not just images, they are testament to a time and its people, a history we should never forget.

Kraków’s Swastikas And Life Under Occupation

Edward Kubalski, a lawyer and local government official, was a chronicler of the German occupation of Kraków. His regular notes recount how German 'Heims’, or homes, proliferated, each tailored to a different occupational group. An officers’ mess was established, alongside postal workers, railway workers, and the police.

„Haus Krakau”, or Krakau House, was set up in the former Secession house at the corner of Św. Anna and Wiślna, decorated in a German style with a large 14th-century engraving of Krakow embellished with various German emblems. The corner café on Karmelicka and Dunajewskiego was converted into a „Soldatenheim„, a soldier’s home, emblematic of the dense imprint the German occupation was leaving on the city.

Reading these words, one is reminded of the occupation memoirs of professor Stanisław Hartman, an eminent mathematician who continued the famous Lviv school tradition in post-war Wrocław.

Having spent the war hiding in Lviv, Warsaw, and Kraków, he recorded his impressions of all three cities. To him, Lviv tried to maintain its composure regardless of the circumstances, while Warsaw’s young men wore jackboots and short canvas jackets as symbols of the city’s resistance.

In contrast, Kraków exhibited a completely different atmosphere. Hartman recalled people in cafes pouring over the „Krakauer Zeitung”, a German newspaper published in the General Government from November 12, 1939 to January 17, 1945.

The undertone in Hartman’s account suggests a certain disdain, but Kubalski’s documentation of the city’s appropriation by German elements provides a different perspective.

Monuments to the Führer

These transformations were carried out against a backdrop of unsettling grandeur. Haunting photos show the Market Square festooned with colossal Nazi flags, brimming with German dignitaries in uniform or civilian attire. Celebrations of the Führer’s birthday or subsequent anniversaries of the war’s commencement took on an unnervingly theatrical air.

Hans Frank, the Governor-General who resided at Wawel, reveled in such pomp and circumstance. In his role, he could indulge his enormous ego. Frank’s self-importance was not lost on his party comrades. Joseph Goebbels noted in his diary, „Frank does not see himself as a representative of the Reich, but rather as a king of Poland.

This will not end well. Frank doesn’t rule; he reigns. He seems to fancy himself a Polish ruler and is surprised when guards don’t salute him as he enters a German official building. Something will have to be done about it.”

Frank’s harsh demeanor left no illusions for the Poles. In an interview for the „Völkischer Beobachter” on February 12, 1940, he made a chilling statement: „If I wanted to put up a poster for every seven Poles shot, Poland would not have enough forests to print them.” On the same day, 180 people were shot in Lublin.

The Krakow exhibition pays significant attention to the authorities of the General Government. This includes not only Frank and his fur-loving wife Brigitte, who repeatedly caused her husband financial difficulties, but also lesser-known officers. Interestingly, Austrians dominated the ranks.

The catalogue informs us that Rudolf Pavlu, an Austrian lawyer and NSDAP member, was appointed head of the Labor Department in the office of the district head, and then the Stadthauptman of Krakow. Egon Hőller, another lawyer and NSD

AP member, was appointed head of the Krakow county in October 1939. This all serves as a reminder of the deep-seated foreign intrusion that shaped Krakow’s landscape during the occupation.

Looting Under Occupation

At this point, we must examine the widespread issue of looting in occupied Kraków. Both state-sanctioned and on a personal scale, looting often took place in direct opposition to the interests of the Third Reich. The widely known stories of the looting of the St. Mary’s altar and the Czartoryski collection typically fail to mention the individual responsible: another Austrian, Kajetan Mühlmann.

- You should definitely read the story behind the Da Vinci painting in Kraków: The Journey of The Da Vinci’s „Lady with an Ermine” to Kraków

An art history graduate and co-organizer of the famed Salzburg music festival, he was officially charged with the tasks of plunder. His counterpart, Dagobert Frey from Wrocław, another art historian, helped compile lists of artwrks to be stolen, greatly aiding Mühlmann.

The scale of corruption is astonishing, with everyone from top officials to simple soldiers engaged in theft. An intriguing story comes from Richard Lauxmann, son of the director of the German Post Office East in the General Government.

His sister, enamored with the abundant and cheap Jewish property on sale, asked their father to acquire some for her. He reacted with indignation, adamantly refusing to allow any stolen Jewish property in their home. This disconnect between understanding and actions persisted in the family even post-war.

The Paradox of Forbidden Interactions

Did German settlers during the occupation truly have no contact with Poles and Jews? Officially, interactions were strictly forbidden and came with severe penalties, including the death sentence. Yet instances of relationships between Germans and Jews, although scandalous, were not unheard of. Fellow Germans would be quick to inherit the wealth left behind by such condemned relationships.

For a time, German Catholics met with Poles in church. The exhibit draws attention to the memoirs of pediatrician Josef Srőder, unjustly forgotten today, who was lauded for his friendship with Poles. He earned the trust of his Polish hospital staff and recounted.

Only in 1943 did the government of the General Government make the Church of Saints Peter and Paul available to German Catholics. Until then, if you wanted to attend a Sunday service, you had to go to a Polish church. And it wasn’t safe at all… Despite the ban, risking danger, we sometimes took part in wonderful, unforgettable services at St. Mary’s Church.

The recollections of Germans who experienced the occupation as children provide a unique perspective. They recall, surprisingly, the city’s vibrant music scene, associating their childhood in Kraków primarily with music.

The General Government Philharmonic was indeed of an exceptional standard, with its first conductor, Hans Rohr, rumored to have been poisoned for being too sympathetic to the Poles.

However, the most poignant memory comes from a seemingly innocuous, static photograph. A German man, presumably a low-level clerk, having occupied the apartment of the distinguished Rostworowski family in Kraków, decided to take a photograph with the evicted owner before she left. His motivation was seemingly to behave correctly.

But how did Róża Rostworowska feel at that moment? How did she manage to act appropriately in such a situation? Why does she, in this deeply disquieting photograph, seem to hold our gaze? This photograph silently portrays the painful paradoxes of life under occupation.

Between the Walls – A Tale of Two Krakóws

The exhibit culminates in a finale where we find ourselves standing between two walls. The first wall displays a virtual map of Kraków, a cityscape made alien through the imposition of German names onto streets, squares, and alleys, echoing an imposed narrative of dominance.

Opposite, the other wall depicts photographs of Kraków’s modest memorial sites, a stark contrast to the grandiose Nazi plans for the city. Among these is a humble monument from Kobierzyn, the outcome of efforts by the Polish-Israeli Society for Mental Health.

This psychiatric hospital in Kraków endured three distinct horrors during the war. First, the intentional starvation of patients; second, the deportation of Jewish patients; and finally, the mass murder of remaining patients on June 23, 1942.

Next to this, a modest obelisk stands on Wodna street, near the Płaszów railway station. Seven Poles were hanged here in reprisal for an attack on a military train passing through the station. The last memorial depicted on this wall is dedicated to the 79 victims of the Dąbie massacre. This senseless slaughter of workers took place merely three days before the Soviet army entered Kraków.

This is a Kraków that most of the Reich’s settlers would have been ignorant of, at a time when the city was meant to become the capital of the German East. This wall of memories serves as a sobering testament to the harsh realities faced by the city and its inhabitants under occupation, a stark contrast to the imposed German narrative of the opposite wall. Thus, between these two walls, visitors are left to contemplate the true history of Kraków, and the resilience of its people in the face of oppression.

References:

- https://krakow.ipn.gov.pl/pl4/edukacja/przystanek-historia/135388,Wojenne-zniszczenia-w-Krakowie-Wrzesien-1939-styczen-1945.html

- https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wyzwolenie_Krakowa